I never expected to become a fantasy writer. As a child and teen, I wasn’t allowed to read or write fantasy books, except for the Narnia series by C. S. Lewis. Fairy tales, myths, and legends were taboo. My parents insisted that my books—on my shelf or in my head—be realistic and preferably religious. In fourth grade, a creative writing assignment for Halloween revolved around the usual topics: ghosts, witches, haunted houses. I wasn’t permitted to dabble in such subjects, so I wrote a story about a plane crash. Everyone died. Suitably grim, I hoped. My teacher was less than impressed, and she wrote in my report card that I had “no imagination.” I had an imagination. When I wrote stories for myself, I could see my characters, and they talked to me. But when I told my parents that, their reaction was negative in the extreme, and I learned to keep the vibrant world in my head a secret. In my forties, I discovered that I have a condition called hyperphantasia, or an overactive imagination. This explains the high-definition imagery in my mind and my ability to perceive places and people in my field of vision, superimposed on reality. Hyperphantasia also explains how real my characters and fictional worlds become to me. When I imagine a scene, I see and hear everything, and with less intensity, experience tastes, textures, and smells. The constant images and incessant internal dialogue in my brain are exhausting, especially when I try to process all of it alongside reality. Writing helps to keep the ideas in manageable order! But as a child, I concealed all that, thinking something was wrong with me. In my late teens, I started writing historical fiction. A novel I wrote in my early twenties, Fool’s Gold, was published online by Reconciliation Press circa 2000. Many years later, when I began the Dragon’s Fire Series with what became the second title, The Rose of Caledon, I intended to produce more historical fiction. It bothered me, though, that I had set the story in a made-up land, instead of placing my characters in England or Ireland. A third of the way through Myrhiadh’s War, when James and Myrhiadh came up with the plot for Dragon’s Fire, a hint of magic crept into the book. I loosened the reins on my imagination that I’d stifled for so long and let it run. I love writing fantasy. The Dragon’s Fire Series is low-fantasy, or magical realism. Through it, I’ve discovered who I am as a writer, and to a great extent, who I am as a person. I’m learning to embrace my imagination instead of viewing it as a disease or even a curse. The novel I mentioned earlier, Fool’s Gold, will be re-released in print at a later date. An editor who went over the text, having never met me or had any interaction with me, commented, “She would make an amazing fantasy writer!” Such a comment 20 years ago would have terrified me. When I wrote Fool's Gold, I didn't dare let my imagination take over, but the editor noticed it, just the same. The Dragon’s Fire Series has taught me to embrace who and what I am, and to appreciate how fun a soaring flight of unhindered imagination can be. I hope my fourth-grade teacher reads them.

0 Comments

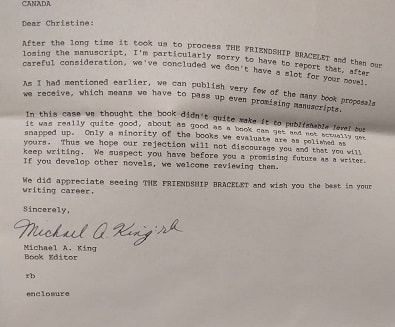

(The following post appeared in a four-part series on Instagram.) I never submitted Dragon’s Fire to an agent, but went straight to self-publishing. I’ve been writing stories since first grade and submitting manuscripts to publishers from the age of thirteen. Back then, I didn’t need an agent, since many reputable companies took submissions from authors. Self-publishing was not yet a popular or affordable thing. I sent out paper manuscripts with self-addressed, stamped return envelopes. I first tried to publish a cliché horse story titled Never Tamed. The manuscript included everything: the wild black stallion, the young teen girl he’d do anything for, the snotty rich neighbor girl with the fancy horse, the threatening, aloof owner of the big stable, the impossible horse race... It’s embarrassing. My stack of rejection letters grew while I kept writing, kept learning, and kept submitting new material. At fifteen, I changed tack and wrote a mystery. That flopped. I was too young to weave anything that would appeal to readers older than ten, and I didn’t write or pitch the manuscript as middle-grade fiction. At sixteen, I tried my hand at a young adult novel of friendship and high school angst. Friendship bracelets were all the rage for teen girls in the late 80s and early 90s, and I titled my story The Friendship Bracelet. It was about long-distance friendships, new relationships, body image, eating disorders, and self-mutilation, told from the point of view of a plain-Jane main character plucked from a big city and dumped into a rural town and its high school where everyone else had known each other since kindergarten. After several rejections, I got a letter. Not a big, thick, returned manuscript, addressed in my handwriting, but a letter! I envisioned my published book before I even opened the envelope. The letter from a submission editor read, “I love this story, and I want to present it to the senior editing team at our next meeting, but I’m embarrassed to say I’ve lost your manuscript. Would you be so kind as to print and send it again at our expense? I’m sorry for the inconvenience.” I printed and mailed another copy with a bill and a thank-you note. For the next several weeks, I lived on a cloud, convinced that if one liked the story, the rest would, too. But after a time, that thick envelope I had learned to dread appeared in the mailbox. It contained my manuscript, a cheque for printing and mailing costs, and another letter from the editor who loved my book. “In this case, we thought the book didn’t quite make it to a publishable level, but it was really quite good, about as good as a book can get and not actually get snapped up. Only a minority of the books we evaluate are as polished as yours. Thus we hope our rejection will not discourage you and that you will keep writing. We suspect you have before you a promising future as a writer.” I was crushed. I cried for days. Then I sent the story out again. No one else ever picked it up. I moved on, wrote new stuff, and the book died in a realm of outdated floppy disks and dog-eared, yellow pages. In my early twenties, I produced a saga of slavery and the Underground Railroad. I shipped off a query and some sample chapters (via the internet!) The prompt response came. “We’re sorry, but at 160,000 words, this manuscript is beyond our capacity to publish...” But this time, the editor included feedback. “We see point of view issues, consistency problems, telling instead of showing, and an overwhelmed plot, but we see a lot of potential in you as a writer. Would you be willing to consider...” Warning bells clanged in my head. Scam! They’re going to ask for money to publish something! Run far, run fast! But no. This publisher asked if I would work for them, producing writing to their specifications, in exchange for one-on-one mentoring. The man offering worked as a teacher of creative writing besides running his publishing house. He asked for no money. I gambled only my time. Best decision I ever made. I worked with and for my mentor for five years, studying the craft of writing, learning to edit on-the-job, and writing historical fiction for children and young adults. I even made some money. This honest little company was the best thing that could have happened to my writing career. I gained the equivalent of a college education in creative writing and editing, published several short stories and study guides, and released a full-length novel titled Fool’s Gold online (no longer available.) I was a step closer to my dream. Someone had seen value in my work and published it for people to read. I was so happy! Then motherhood hit, and the demands of babies swamped the writing. I knew things would get worse, not better, and in 2002, I resigned my position to focus on the challenges of being a homeschooling mom. Fourteen years passed. I flexed my writing muscles by composing a creative Christmas letter every year. I taught my kids grammar, spelling, and punctuation, and critiqued their writing assignments, trying desperately to remember that they were children, not clients. In the summer of 2016, I couldn’t hold back anymore. Even though I knew the writing urge would consume me, I gave in and started the Dragon’s Fire Series. I loved the entire experience. I felt like I had found Me again after losing her somewhere in the diapers, dishes, and disasters. Nothing I’d written before had been so fun—my first accidental foray into fantasy (more on that next month). With each new story, the books got better. When I decided to publish the series, I considered seeking an agent but ruled against it. I didn’t want to put myself through the wringer again: the research, the querying, the endless strings of rejections, the trials of hoping today might be the day. Publishing is a subjective field. Your book has to be exciting and well written, and you need a generous dose of luck to hit the right editor on the right day. I was having fun writing these books, and I didn’t want to kill that. These stories mustn’t die like The Friendship Bracelet in a stack of rejection letters and a crush of broken dreams. I wanted to share them. If they sold, great, if they didn’t, no harm done. So I self-published. Readers love them. It’s still my dream to do traditional publication one day. I’ve got a manuscript in the works that I might send to agents over the next year or two. On social media, I call it my Naughty Pleasure: a standalone, young adult novel with a unique twist that I think may sell very well. But until then, I sit with my feet up on my coffee table, running my little publishing empire, and editing for a new publishing house and some freelance clients. I’ve got readers between the ages of nine and 84 begging for more, and I’m happy. That’s what matters. |

Archives

March 2024

EventsCheck out my interview with blogger Fiona Mcvie! https://wp.me/p3uv2y-75n

|